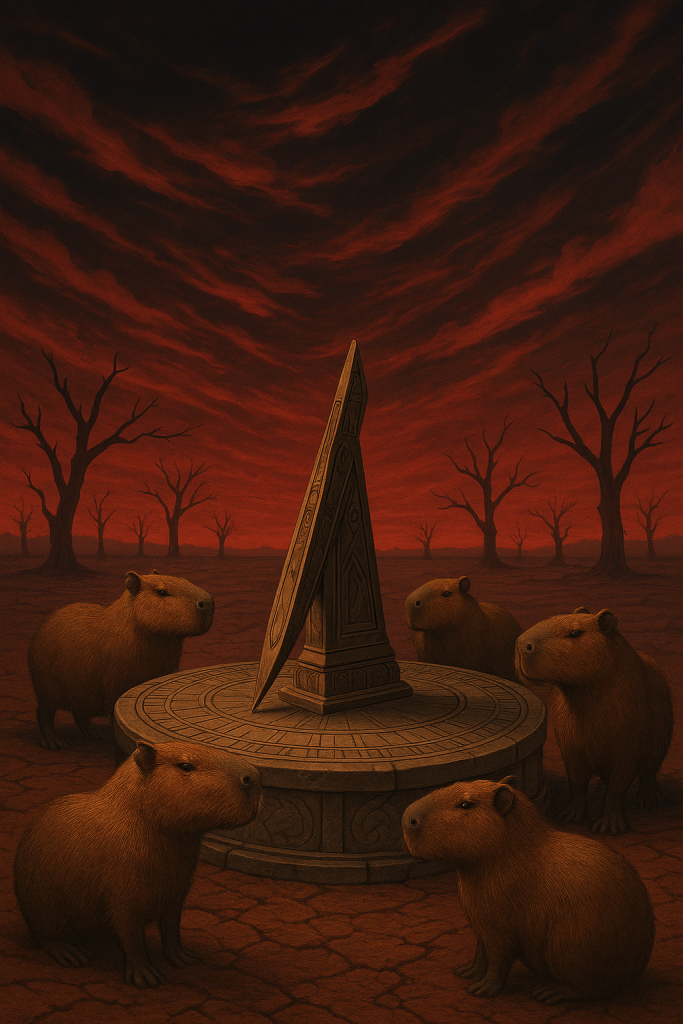

They stood in their mute encirclement of the old stone dial whose gnomon cut the sky like some blade buried to the hilt, watchful and unknowing in the ruin of that bloodred firmament where the last clouds moved like smoke over a charred plain and the trees stood stripped and dead, each branch a black hieroglyph inscribed upon the horizon of a world that had outlived its own design, the beasts patient and stolid as though they had always been there and would remain long after the monument had crumbled to dust, their vigil primal and inexplicable, witnesses to some covenant made before memory, before time itself had learned to mark its passing on the sundial face of that strange pillar.

The cat regarded him across the rust-colored waste with eyes like amber coins struck in some ancient forge. Behind them the ringed planet hung enormous in the darkling sky, a judge presiding over dominions of dust. The creature beside him stood in its alien perpendicularity, eyestalks searching the horizon for what sustenance this world might yield or what communion might be drawn from the silence.

They were pilgrims both in a land that knew no scripture. The cat’s fur held the darkness of collapsed stars and its red collar was the only covenant between the world it had known and this one. The companion creature, orange as oxidized iron, as the very soil beneath them, seemed born of this place, extruded from the planet’s own weird geometry.

What word could pass between such beings? What language obtains in the transit between one world and another? They sat in that vast cathedral of emptiness and the wind if there was wind carried no answer. Only the patient mathematics of orbit and decay, the supreme indifference of the cosmos to the small and the breathing, the furred and the strange, all that moves and must one day cease to move upon the surface of ten trillion worlds or one.

The cats sat upon Andy narwhal in the crystalline dark, their caps the colors of some merchant caravan out of antiquity, rainbow-banded like Joseph’s coat. Above them the auroral light moved in great sheets across the firmament, green and luminous, a celestial fire that burned without consuming. The beast beneath them cleaved through black waters, its horn a pale tusk jutting forward like the spear of some drowned knight errant.

The orange cat’s eyes held the simple faith of all creatures who know not their fate. The black cat watched with an older knowing. They rode the leviathan through that polar waste beneath skies no different than those which men had watched since the world was made, wondering at their brief passage through the dark and whether any hand had set the stars or whether the stars themselves were but another kind of wanderer, alone and purposeless in the void.

The water rolled away from the narwhal’s passage in folds of deepest cobalt. What lay beneath no man could say. What lay ahead the same. And still they rode.

Long ago, when the moon was still young, a calico guardian fell asleep on a cushion of stone. Around her crept goblins with sacks of gold and pots of clay, hoping to steal while she dreamed. But the cat’s slumber was deeper than time itself, and her breath was the rhythm that kept the world from unraveling. The goblins soon discovered that each coin they lifted crumbled into sand, each jewel turned to ash. They understood then that the guardian was dreaming for them all—that her silence was the thread that stitched memory to reality. So they stopped their thieving and kept vigil in the shadows, protecting the cat who protected them, waiting for a dawn that would never come as long as she slept.