A Rationalist Case for Absolute Monism

From Plotinus to classical theism to Spinoza, philosophers have posited a supreme metaphysical entity—the One, God, or Substance—to ground reality and explain existence. This post argues that the very distinctions these systems depend upon collapse under sustained rationalist scrutiny. By applying the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR) rigorously, I demonstrate that all three major frameworks—Plotinian emanation, Spinozistic necessitarianism, and Thomistic theism—contain fatal explanatory gaps. The only position that survives this collapse is monism: reality is necessary and one, without intermediary beings, divine personhood, metaphysical hierarchy or modal hooey. What remains is not God, but simply what is.

I. Mapping the Metaphysical Landscape

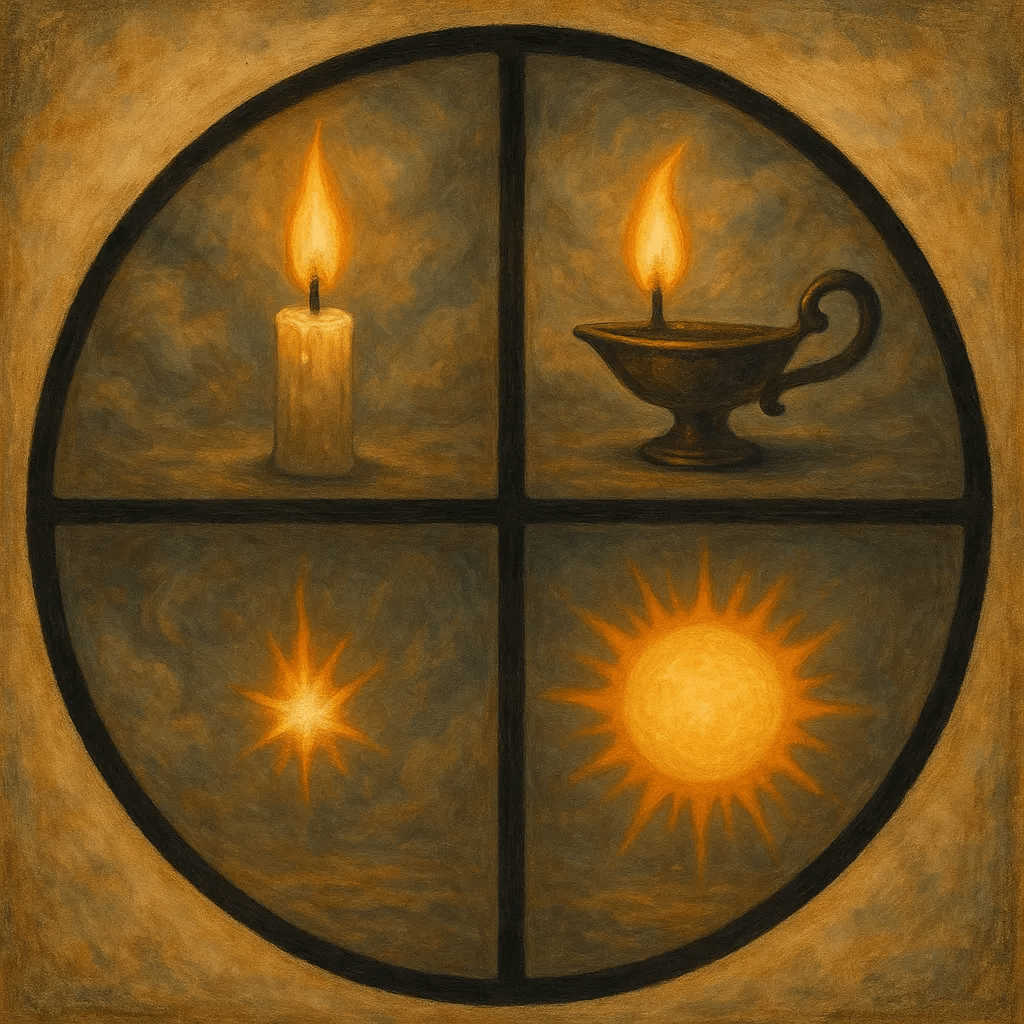

Before dismantling these systems, we must understand their architecture. Consider three major positions on a spectrum of explanatory density:

Plotinus’ One — beyond being, beyond intellect, overflowing without self-determination.

Classical Theistic God — metaphysically non-composite, timeless, immutable, impassable, and freely creating.

Spinoza’s God — absolutely infinite substance determined solely by its own essence; nature is necessity.

The tensions lie in how each answers (or refuses to answer) the rationalist’s question: ‘In virtue of what?’

1.1 Ontological Status: Being, Beyond-Being, or the Only Being

Plotinus’ One — literally not a being, not even an entity. Radically simple: no internal structure, no attributes, no parts, no thought. All positive description is metaphor; the One is what the intellect sees when it stops trying to articulate. The One is uncaused, not by necessity but by transcendence.

Classical Theistic God — a supreme being, perfect, personal, omniscient, omnipotent. God has attributes (even if simple in scholastic metaphysics). God wills, knows, loves, judges; creation is a free act. God is both intellect and will.

Spinoza’s God — being itself, the one infinite substance with infinite attributes. Not a person; not a transcendent source; not outside the world. Nature equals God equals the necessary structure of reality. All distinction collapses into modes of the one substance.

Comparative snapshot: Plotinus offers the beyond; classical theism offers a supreme being; Spinoza offers the only being.

1.2 Causation: Emanation, Volition, or Necessity

Plotinus — causation is emanation: the One overflows into Intellect, which overflows into Soul. The One cannot do otherwise, but not because of inner necessity; more like metaphysical pressure.

Classical Theism — causation is free creation ex nihilo. God might have chosen otherwise; creation is not necessary.

Spinoza — causation is strict necessity: from the necessity of the divine nature infinite things follow. No choice, no contingency.

Thus we have: Plotinus offering spillage, theism offering choice, and Spinoza offering necessitation.

1.3 Intelligibility Under PSR Pressure

Here the Parmenidean lens does its devastating work.

Plotinus — The One is beyond intelligibility. You cannot say why the One emanates; you cannot even say why it is what it is. This violates the strong PSR: the One is precisely the sort of brute posit the rationalist cannot allow.

Classical Theism — God freely chooses creation, freely wills certain goods, freely permits evil. Each free decision creates pockets of brute contingency. The rationalist asks: In virtue of what does God choose this world rather than another? No answer preserves classical divine freedom without violating PSR. Result: classical theism stands on voluntarist bruteness.

Spinoza — Spinoza preserves the PSR absolutely. No brute facts, no free divine choices, no transcendent will. God is the necessity of being itself. Result: maximal intelligibility.

Summary: Plotinus fails rationalist intelligibility (beyond being and explanation); theism fails it (arbitrary divine free will); Spinoza appears to satisfy it (necessity all the way down).

But does Spinoza survive deeper scrutiny? (“Proofs of God’s Existence? Paging Spinoza! And why not even he can help you.”)

II. The Positive Case: Why Bare Monism Surpasses All Middle-Beings

Now we proceed to the core argument. Why add a special metaphysical entity—Plotinus’ One, Spinoza’s God, or classical theism’s Pure Act—when you can have the explanatory power without the metaphysical inflation? This section presents eight independent arguments for bare monism over any divine intermediary.

2.1 The PSR Eliminates All Distinctions—Including God

The most devastating argument comes from applying the PSR consistently. If every distinction requires an explanation, then the distinction between God and world, between God’s essence and activity, between modes and substance, between the One and its emanations, between Pure Act and creation—each needs justification. But any justification introduces more distinctions, requiring further justification. This is Bradley’s regress applied to theology.

The only stable resting point is no distinctions at all. That means no God/world distinction, no intellect/extension distinction, no essence/existence distinction, no emanation hierarchy. Once all distinctions collapse, what is left? Just Being as such, full stop.

Plotinus tries to resolve the regress by pushing the One beyond being, making it uninterpretable. Spinoza tries to resolve it by allowing infinite attributes. Classical theism tries with negative theology and divine simplicity. All fail because distinction itself is the problem. The PSR favors pure monism over any conception of God.

2.2 Explanatory Economy: Any God Adds Mystery Rather Than Removing It

Plotinus adds a One that we cannot describe but which somehow emanates Nous and Soul. Spinoza adds a God with infinite attributes, only two of which humans know. Classical theism adds a pure act that is totally simple yet somehow contains intellect, will, and the ground of all modal truths. All three introduce highly specific, explanatory-heavy, ontologically ambitious entities.

But none of these entities explains anything that bare monism does not already explain. If the question is ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’, the honest answer is: Because there cannot be nothing. The existence of being requires no explanation; nonbeing does. To add a God is to duplicate necessity: necessary being (God) plus the necessary existence of that being. Whereas pure monism says: Being is necessary; nothing else exists to explain. No additional entity is needed.

2.3 The Problem of Explanatory Elites

Every divine monism contains the same hidden assumption: there must be one special kind of thing that grounds everything else. But introducing a special category, a metaphysical elite, is inherently unstable under the PSR. Why should the One have the power to cause Nous? Why should Spinoza’s Substance have infinite attributes rather than one? Why should pure actuality have the will to create anything? Each of these attributes is unshared, primitive, unexplained. They violate the very explanatory scruples they seek to defend.

Pure monism says: there is no metaphysical aristocracy, no special status, no elite being. Just what is, without hierarchy. This is the most stable position from an anti-arbitrariness standpoint.

2.4 The Metaphysical Middleman Is Illusion

Consider each supposed function of God:

Unity/Explanation: Does God unify things? No more than monism itself does.

Necessity: Is God supposed to be the necessary ground? But necessity does not require a bearer. It simply means: cannot be otherwise.

Causation: Is God needed as cause? In a monistic system, cause is just the structure of being itself.

Order/Rationality: Is God needed as architect? No more than geometry needs a designer.

Value/Goodness: Plotinus and Aquinas load the Absolute with normative weight. But monism says: value is a projection; being is neutral.

What God is supposed to do, monism does.

2.5 God Is Just a Hypostatization of Necessity

At bottom: Plotinus’ One equals unity, Spinoza’s God equals necessity, classical theism’s God equals pure actuality. All three equal the necessary structure of reality. But then why anthropomorphize necessity? Why personify unity? Why not say directly: Reality is necessarily one. Period.

Everything else is mythologizing necessity. God is the reification of an abstraction. Necessity itself does not need to be pinned on an entity.

2.6 Why Philosophers Keep Inventing the Middle-Being

Why do even rigorous rationalists insert a metaphysical middle-being when their systems do not need it? Several explanations present themselves:

Fear of Metaphysical Nakedness: Bare monism is austere and offers no comfort: no higher being, no metaphysical parent, no intelligence behind order, no source of meaning, no providence. Even rationalists hesitate to say: Reality just is. It explains itself. There is nothing above it or below.

Cognitive Bias for Hierarchy: Human cognition loves levels, order, higher and lower beings, top-down explanations. Bare monism abolishes hierarchy. That feels unintuitive, even threatening. So philosophers construct the One to Nous to Soul, Substance to Attributes to Modes, God to Angels to Creatures. These are comfort structures, not necessities of reason.

The Desire for a Terminus That Is Like Us: Plotinus’ One is beyond mind but still good. Spinoza’s God thinks. Classical theism’s God thinks, wills, loves. These are projections of human categories upward, because we subconsciously want the universe to be conscious, order to be intentional, existence to be meaningful. Bare monism refuses this anthropocentric impulse.

The Rhetorical Power of the Divine Label: Calling the Absolute ‘God’ buys cultural legitimacy, emotional resonance, philosophical gravitas. But the label is linguistic camouflage disguising the fact that the work is done by necessity, not by a divine agent.

2.7 Bare Monism Avoids All Classical Problems

There is no need to solve divine simplicity paradoxes, divine freedom paradoxes, the emanation hierarchy, the problem of evil, the will/knowledge/intellect compatibility problems, modal collapse objections, contingency versus necessity, or the relation between attributes and substance. Bare monism eliminates all of them. Why? Because it eliminates the middle-being. There is no metaphysical manager. Just reality.

2.8 Conclusion of the Positive Case

If you accept the PSR, anti-arbitrariness, rejection of brute facts, intelligibility, and necessity, then the simplest and least metaphysically baroque view is this: There is one necessary reality. It has no distinctions. It is not a being—it is Being. It is not God—it is what there is.

Plotinus, Spinoza, and classical theism all carry unnecessary metaphysical baggage: divine names, hypostatic structures, privileged entities. The cleanest version is the one that survives the Parmenidean ascent: Reality is necessary and one. There is nothing else to explain. Adding God is metaphysical ornamentation.

III. The Formal Reductio: Why God Is Incoherent Under the PSR

This section presents a formal proof showing that the very concept of God is incompatible with the PSR. This reductio is neutral between classical theism’s God, Spinoza’s God, and Plotinus’ One. It refutes all of them.

3.1 Definitions and Setup

Let PSR be the principle that every fact F has a complete explanation. Let D be the divine being (One, God, or Substance). Let W be the world (finite beings, modes, emanations, etc.). Let Dist(X, Y) mean X is really distinct from Y (not identical).

Assume that D exists and is distinct from W, as all three systems claim in some form: Plotinus through absolute transcendence, Spinoza through the substance/mode distinction, and classical theism through the creator/creation distinction.

3.2 The Reductio Argument

Premise 1: If Dist(D, W), then the distinction must have an explanation (by PSR).

Premise 2: The explanation of Dist(D, W) must be either internal to D or external to D. There are no other options.

Case A: Explanation Is Internal to D

Suppose the distinction arises from D’s internal nature. Then D’s internal nature includes differentiation: some aspect A explains why D is not equal to W. But if D has internal differentiation, then D is composite. If D is composite, D is not simple. If D is not simple, D is not the One, not Pure Act, not Substance. Contradiction.

Thus D cannot internally explain its distinction from W. (For Plotinus, the One cannot contain distinctions; for Spinoza, substance has no internal differentiation; for classical theism, God has no internal composition.)

Case B: Explanation Is External to D

Suppose the distinction between D and W is explained by something outside D. Then some entity E, distinct from D, explains Dist(D, W). But then D is not the ultimate explanation. Therefore D is not divine (not the One, not Pure Act, not the fundament of being). Contradiction.

Thus D cannot externally explain the distinction either.

3.3 The Devastating Conclusion

The distinction between D and W cannot be explained internally (violates simplicity) or externally (violates ultimacy). Therefore Dist(D, W) violates PSR and is impossible.

Thus: Either D equals W (Spinoza’s immanent collapse), or both D and W collapse into something more basic (Parmenidean monism), or there is no D distinct from W (bare monism/bare necessity).

But if D equals W, then the term ‘God’ does no metaphysical work. It adds no distinctions (forbidden under Case A). It adds no explanatory power (forbidden under Case B). It introduces misleading conceptual baggage.

Therefore: The concept ‘God’ is explanatorily redundant and PSR-incoherent. The only consistent position is bare monism/bare necessity.

What Remains After the Collapse

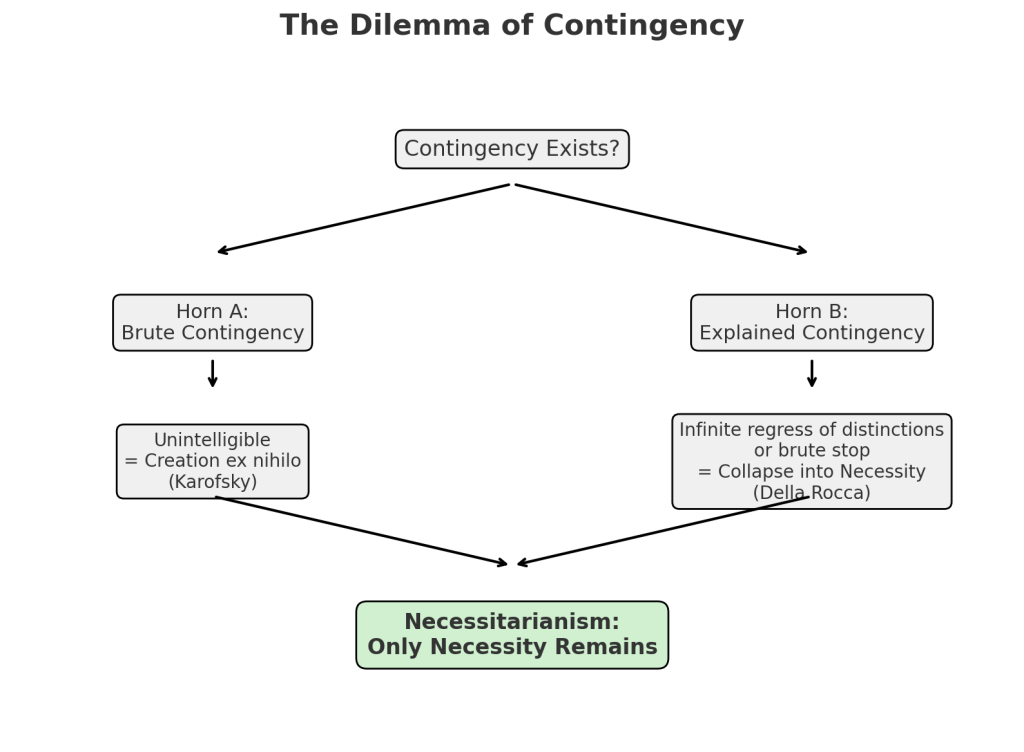

We have traced the rationalist’s path through three major metaphysical systems. Plotinus offers the One beyond being, but this transcendence purchases explanatory power at the cost of intelligibility—the One becomes a brute posit, violating the very demand for reasons it was meant to satisfy. Classical theism offers a personal God whose free will creates the world, but this freedom introduces arbitrary divine choices that cannot be explained without destroying the freedom itself. Spinoza comes closest to rationalist purity by eliminating divine will and embracing necessity, yet even Spinoza’s distinction between substance and modes, between infinite attributes and their expressions, cannot withstand sustained PSR scrutiny.

The formal reductio demonstrates this with precision: any distinct divine being, whether transcendent or immanent, whether personal or structural, cannot explain its distinction from the world without either becoming composite (losing simplicity) or depending on something external (losing ultimacy). Either horn of the dilemma proves fatal.

What survives this collapse? Not a divine being, not a One, not even Spinoza’s God. What survives is simply this: Reality is necessary. Reality is one. There is nothing else to explain because nothing else exists to do the explaining. Necessity requires no bearer, unity needs no unifier, being demands no ground beyond itself.

This is bare monism—monism without magic, necessity without necessitator, unity without metaphysical manager. It is the position that all rationalist systems approach but fail to reach, held back by residual anthropomorphism, theological inheritance, or the simple human desire to find consciousness at the foundation of things.

The concept of God, in all its philosophical forms, turns out to be an elaborate way of saying: things are as they must be. Once we recognize this, we can dispense with the intermediary and state the truth directly. There is what is. That is all. That is enough.

Bibliography

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologiae. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Benziger Bros., 1947.

Bradley, F. H. Appearance and Reality: A Metaphysical Essay. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 1897.

Curley, Edwin, and Gregory Walski. “Spinoza’s Necessitarianism Reconsidered.” In New Essays on the Rationalists, edited by Rocco J. Gennaro and Charles Huenemann, 241–262. Oxford University Press, 1999.

Della Rocca, Michael. The Parmenidean Ascent. Oxford University Press, 2020.

— “PSR.” Philosophers’ Imprint 10, no. 7 (2010): 1–13.

—”Rationalism Run Amok: Representation and the Reality of Emotions in Spinoza.” In Interpreting Spinoza: Critical Essays, edited by Charlie Huenemann, 26–52. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Feser, Edward. Five Proofs of the Existence of God. Ignatius Press, 2017.

— Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction. Editiones Scholasticae, 2014.

Gerson, Lloyd P. Plotinus. Routledge, 1994.

Jablonski, Petronius. “Proofs of God’s Existence? Paging Spinoza!“

Kretzmann, Norman, and Eleonore Stump, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Aquinas. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays. Translated and edited by Roger Ariew and Daniel Garber. Hackett Publishing, 1989.

Melamed, Yitzhak Y. “Spinoza’s Metaphysics of Substance: The Substance-Mode Relation as a Relation of Inherence and Predication.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 78, no. 1 (2009): 17–82.

Parmenides. “On Nature.” In The Presocratic Philosophers, edited by G. S. Kirk, J. E. Raven, and M. Schofield, 239–262. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Plotinus. The Enneads. Translated by Stephen MacKenna, abridged with introduction and notes by John Dillon. Penguin Books, 1991.

Pruss, Alexander R. The Principle of Sufficient Reason: A Reassessment. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Schaffer, Jonathan. “Monism: The Priority of the Whole.” Philosophical Review 119, no. 1 (2010): 31–76.

Spinoza, Baruch. Ethics. Translated by Edwin Curley. In The Collected Works of Spinoza, vol. 1, edited by Edwin Curley. Princeton University Press, 1985.

— Theological-Political Treatise. Translated by Jonathan Israel and Michael Silverthorne. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Stump, Eleonore. Aquinas. Routledge, 2003.